The Emotional Experience of Grief

The Emotional Experience of Grief

Grief is often mistaken for depression or sadness—but it’s far more complex. It’s not a single emotion, but a full spectrum of emotional responses that can include sadness, relief, numbness, gratitude, guilt, anger, fear, or joy—often several at once

It’s common—and entirely normal—to feel seemingly opposing emotions at once, like longing and gratitude. Grief can encompass the full spectrum of human emotion, but a few stand out as especially important to understand more deeply.

Anger

Anger is a common and healthy part of grief.

“Anger is sort of the hidden emotion in grief. A lot of grieving people are incredibly angry for a lot of different reasons.”

Anger can be what's known as a secondary—or "surface"—emotion. While it can be a primary emotion, it often arises in response to deeper feelings like sadness, fear, or helplessness.

When someone expresses anger, especially in the context of grief, it may be masking more vulnerable emotions underneath.

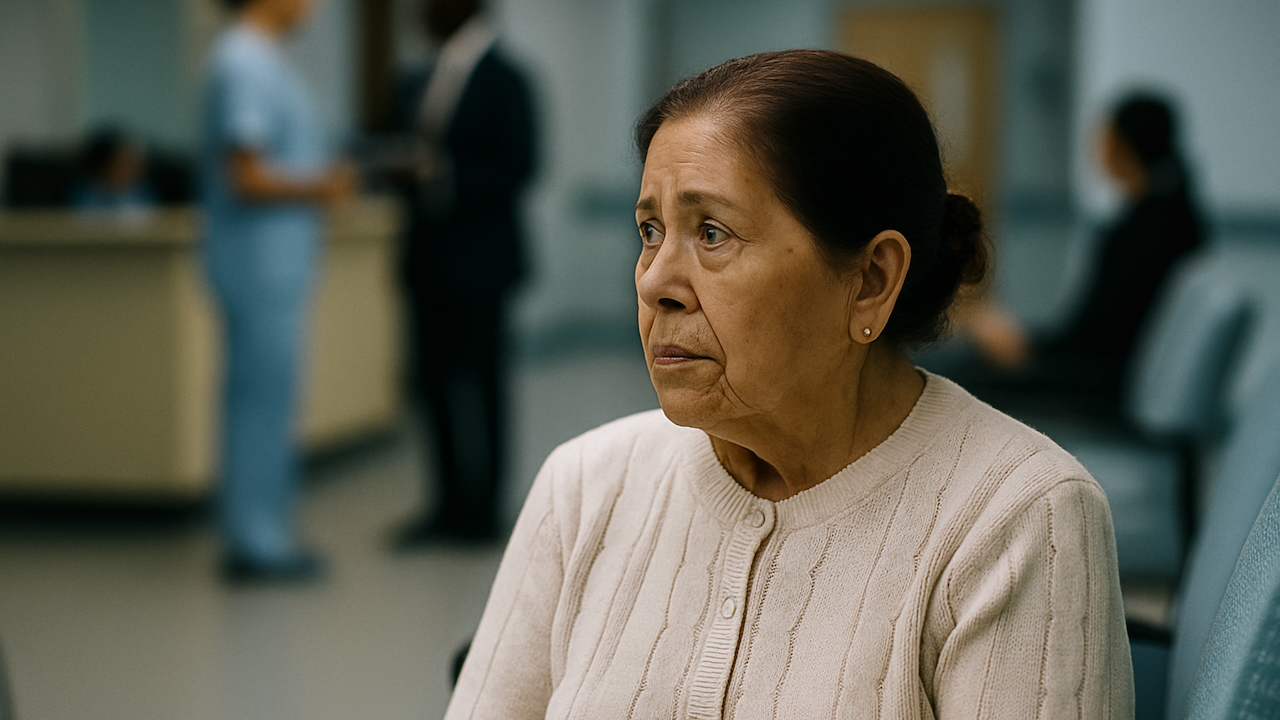

Zee Wolters, bereaved daughter, is featured in the WPSU initiative Speaking Grief

Recognizing and Responding to Grief-Related Anger

In healthcare settings, recognizing that anger is a common—and often misunderstood—expression of grief can improve communication and reduce harm.

"Anger is pain's bodyguard.”

How It Shows Up

Grief-related anger may be direct and intense with patients or their families—such as yelling, cursing, or physical agitation. Among colleagues, it often presents more subtly, through impatience, curt replies, or sarcastic remarks.

Hot anger involves overt, intense reactions (e.g., shouting, slamming doors, physical outbursts).

Cold anger is more restrained and indirect (e.g., sarcasm, withdrawal, silence, or passive resistance).

How to Respond

If someone’s anger feels disproportionate or directed at you, pause and consider: this may be grief—not personal. Acknowledge their distress without accepting harmful behavior.

It’s possible to assert a boundary in a way that is grief informed:

“I can see this is incredibly hard. I want to support you—and we need to keep this a respectful space.”

“Hey, that felt a little harsh. I know you’re hurting and I want you to know that I’m on your side.”

Often simply acknowledging the anger can help defuse it.

Abuse is never acceptable, with or without grief.

Example 1: Patient or Family Member (Hot Anger):

Situation: A parent yells during a care conference.

Response:

"I can hear how frustrated and overwhelmed you’re feeling. This is an incredibly hard situation, and I want you to know we’re here to support you. Let’s take a moment and talk through what’s most important right now.”

Example 2: Colleague (Cold Anger)

Situation: A team member gives you the silent treatment after a care disagreement.

Response:

"I’ve noticed some distance between us lately. If I’ve said or done something that added to your stress, that wasn’t my intent. I know this work can carry a lot of invisible weight, and I’m open to talking when you’re ready."

Example 3: Setting a Grief-Informed Boundary

Situation: Repeated snide remarks or hostility from a grieving coworker or client.

Response:

"I understand this is an incredibly hard time, and I want to be supportive. At the same time, some of the comments lately have felt pointed. Let’s find a way to communicate that honors what you’re going through and allows us to work together more effectively."

Fear

Fear is often part of grief. Fear of life without the person. Fear of forgetting. Fear of what’s ahead. For many, grief shakes the foundation of what felt certain.

“No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear.”

In clinical settings, this fear may show up as anxiety, avoidance, or even anger. Recognizing fear as part of the grieving process helps us respond with empathy—not judgment.

Fear is closely linked to another “f-word”: failure.

For many healthcare providers, fear and failure are closely intertwined. Even when outcomes are medically inevitable, the death of a patient can feel like a personal failure—especially in a culture that values cure over comfort. This unspoken pressure can make it harder to talk about grief, harder to process it, and harder to support others through it.

“Every time a patient dies, a part of me feels like I failed.”

Recognizing this dynamic isn’t a weakness—it’s a step toward healthier, more human-centered care.

Sadness

Sadness is one of the most expected emotions of grief. But even though it’s common, it doesn’t always show up the way we anticipate.

Some people cry easily and often; others may feel flat, restless, or emotionally heavy without shedding tears. In healthcare settings, sadness can surface in quiet moments: a clenched jaw, a heavy sigh, or a sudden wave of exhaustion after a shift.

However it appears, sadness is a normal, healthy response to loss. It reflects the love, meaning, or connection that’s been disrupted. Try to let it in—without rushing to fix or avoid it.

Grief and depression can share overlapping features—like sadness, sleep disruption, or loss of interest—but they are not the same.

Grief is a natural response to loss. It tends to fluctuate, often triggered by reminders, and may include moments of joy or connection.

Depression is a clinical condition marked by persistent low mood, hopelessness, and impaired functioning.

Studies, including randomized controlled trials, have shown that antidepressants do not significantly reduce core grief symptoms such as yearning, sadness tied to the specific loss, or emotional pain related to missing the person.

If a grieving person shows signs of sustained despair, self-harm, or disconnection from daily life, a mental health assessment may be warranted—but grief alone is not a disorder.

Joy

A common misconception is that grief only looks like sadness, anger, or despair. But the emotional reality of grief is far more layered. People who are grieving may also experience moments of levity, laughter, gratitude, or joy—and that doesn’t mean their grief has ended.

Jack StockLynn is a bereaved son who was interviewed for the WPSU initiative Speaking Grief

Zee Wolters is a bereaved daughter who was interviewed for the WPSU initiative Speaking Grief

Why this matters in healthcare

Patients, families, and even colleagues may smile or joke in the midst of profound grief. These expressions are not evidence that someone is “fine” or “over it.” In fact, many grieving people feel pressure to appear okay—masking their ongoing pain to meet others’ expectations.

Grief and joy are not opposites—they can exist side by side. A person may laugh in one moment and cry in the next. Both responses are valid. For clinicians and caregivers, recognizing this duality is key to offering respectful, sustained support.

Don’t assume that smiling means healing is complete. If you see a grieving patient or colleague expressing joy, let it be a welcome moment—but not a reason to withdraw support.

Numbness

Numbness is a common—and often overlooked—response to grief. Feeling emotionally neutral or detached doesn’t mean you’re “doing it wrong” or that the loss hasn’t affected you. It may be your brain’s way of protecting you until you’re ready to process the pain.

This can be especially true in healthcare settings, where the demands of the job often require compartmentalizing emotions to focus on patient care.

Grief doesn’t always follow a visible or expected path. Be gentle with yourself—and know that emotions may surface later, in ways you don’t anticipate.

No One Way to Feel

Grief is a complex emotional experience. These emotional waves don’t just affect how we feel; they also impact how we think, focus, and function.