Understanding Grief as a Healthcare Professional

The Emotional Experience of Grief

Grief is often mistaken for depression or sadness but it’s far more complex. It is full spectrum of emotional responses that can include sadness, relief, numbness, gratitude, guilt, anger, fear, or joy, often several at once

It’s common and entirely normal to feel seemingly opposing emotions at once, like longing and gratitude. Grief can encompass the full spectrum of human emotion, but a few stand out as especially important to understand more deeply.

Anger

Anger is a common, natural, and healthy part of the grief experience.

According to the Cambridge English Dictionary, anger is “a strong feeling that makes you want to hurt someone or be unpleasant because of something unfair or unkind that has happened.”

Since loss often feels unfair or even cruel, it makes sense that anger frequently accompanies grief.

“Anger is sort of the hidden emotion in grief. A lot of grieving people are incredibly angry for a lot of different reasons.”

While anger can be a primary emotion, it can also be what's known as a secondary, or "surface," emotion, arising in response to deeper feelings like sadness, fear, or helplessness. This means that when someone expresses anger, especially in the context of grief, it may be masking more vulnerable emotions underneath.

Anger Can Even Be Surprising for the Person Who is Grieving

The person who is grieving may be surprised by how frequently and easily anger surfaces for them. In this clip from the public media initiative Speaking Grief, a griever named Zee Wolters describes her experience with anger after her mother's death.

In healthcare settings, recognizing that anger is a common and often misunderstood expression of grief can improve communication and reduce harm.

How It Can Show Up

Grief-related anger may be direct and intense with patients or their families and may include behaviors like yelling, cursing, or physical agitation.

Among colleagues, it often presents more subtly, through impatience, curt replies, or sarcastic remarks.

Hot anger involves overt, intense reactions (e.g., shouting, slamming doors, physical outbursts).

Cold anger is more restrained and indirect (e.g., sarcasm, withdrawal, silence, or passive resistance).

If someone’s anger feels disproportionate or directed at you, pause and consider: this may be grief, not personal. Acknowledge their distress without accepting harmful behavior.

Scenario 1: A parent yells during a care conference for their child.

Response:

"I can hear how frustrated and overwhelmed you’re feeling. This is an incredibly hard situation, and I want you to know we’re here to support you. Let’s take a moment and talk through what’s most important right now.”

Scenario 2: A team member gives you the silent treatment after a care disagreement.

Response:

"I’ve noticed some distance between us lately. If I’ve said or done something that added to your stress, that wasn’t my intent. I know this work can carry a lot of invisible weight, and I’m open to talking when you’re ready."

Scenario 3: Repeated passive aggressive remarks from a grieving coworker.

Response:

"I understand this is an incredibly hard time, and I want to be supportive. At the same time, some of the comments lately have felt pointed. Let’s find a way to communicate that honors what you’re going through and allows us to work together more effectively."

Often simply acknowledging the anger can help defuse it.

Abuse is never acceptable, with or without grief.

Fear

Fear is often part of the grief experience. Fear of life without the person. Fear of forgetting. Fear of what’s ahead. For many, grief shakes the foundation of what felt certain.

“No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear.”

Patients and Their Supporters

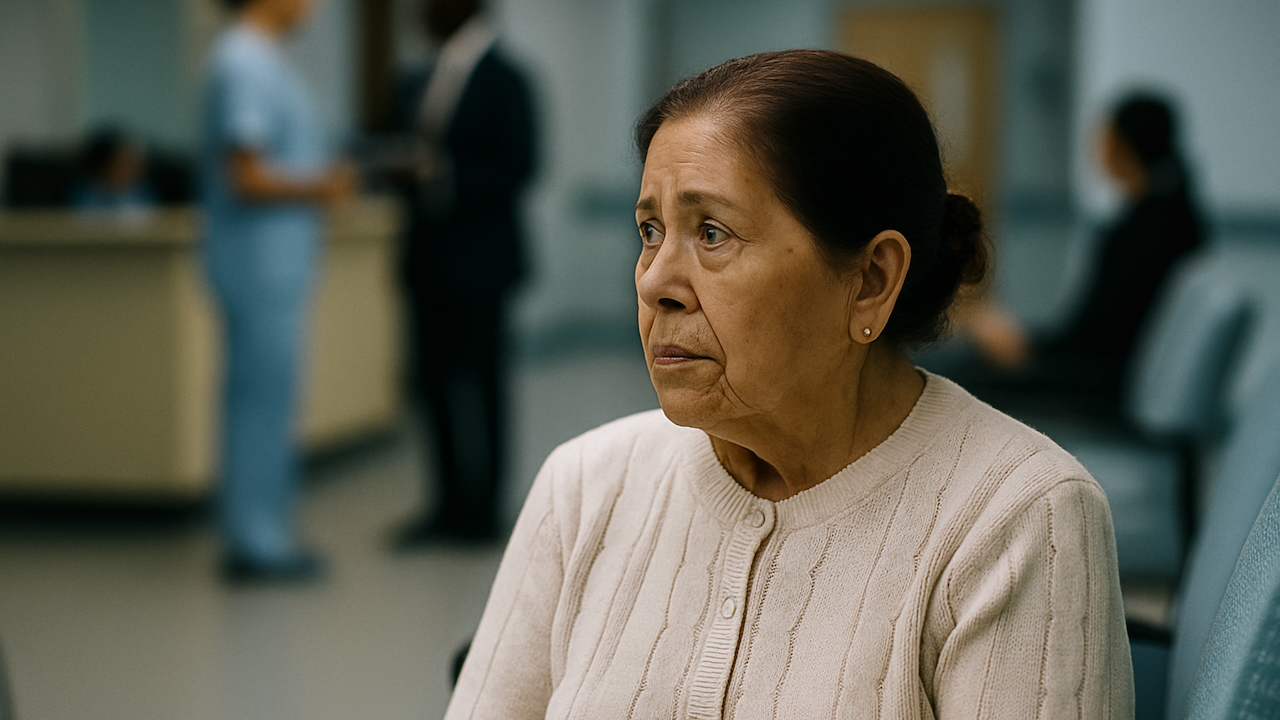

In healthcare settings, grief-related fear often stems from uncertainty. Whether it's uncertainty about a prognosis or uncertainty of what life will look like after the death of a significant other, recognizing that fear is part of the grief experience is an important aspect of compassionate care.

Patience, understanding, and transparency can be great medicine for grief-related fear.

In this interview clip for The Apologies Podcast, a pediatric ICU nurse Hui-wen Sato shares how her breast cancer diagnosis gave her a deeper understanding of just how overwhelming uncertainty can feel from the patient’s side.

Healthcare Professionals

For many healthcare providers, fear is closely linked to another “f-word”: failure.

Even when outcomes are medically inevitable, the death of a patient can feel like a personal failure. This unspoken pressure can make it harder to talk about grief, harder to navigate it, and harder to support others through it.

“Every time a patient dies, a part of me feels like I failed.”

Reframing outcomes and normalizing the challenges that can come from working in high-stakes environments can help mitigate the fear of failure. This can be especially true if you're in a leadership role where others rely on you for guidance or if you are an early-career professional navigating performance expectations.

Joy

A common misconception is that grief only looks like sadness, anger, or despair. But the emotional reality of grief is far more layered. People who are grieving may also experience moments of levity, laughter, gratitude, or joy and that doesn’t mean their grief has ended.

Jack StockLynn is a bereaved son who was interviewed for the WPSU initiative Speaking Grief

Zee Wolters is a bereaved daughter who was interviewed for the WPSU initiative Speaking Grief

Be mindful of assumptions

Patients, families, and even colleagues may smile or joke in the midst of profound grief. These expressions are not evidence that someone is “fine” or “over it.” In fact, many grieving people feel pressure to appear okay, masking their ongoing pain to meet others’ expectations.

Grief and joy are not opposites; they can exist side by side. A person may laugh in one moment and cry in the next. Both responses are valid. For clinicians and caregivers, recognizing this duality is key to offering respectful, sustained support.

Don’t assume that smiling means healing is complete. If you see a grieving patient or colleague expressing joy, let it be a welcome moment but not a reason to withdraw support.

Sadness

Sadness is one of the most expected emotions of grief. But even though it’s common, it doesn’t always show up the way we anticipate.

Some people cry easily and often; others may feel flat, restless, or emotionally heavy without shedding tears. In healthcare settings, sadness can surface in quiet moments: a clenched jaw, a heavy sigh, or a sudden wave of exhaustion after a shift.

However it appears, sadness is a normal, healthy response to loss. It reflects the love, meaning, or connection that’s been disrupted. Try to let it in—without rushing to fix or avoid it.

Grief and depression can share overlapping features like sadness, sleep disruption, or loss of interest but they are not the same.

Grief is a natural response to loss. It tends to fluctuate, often triggered by reminders, and may include moments of joy or connection.

Depression is a clinical condition marked by persistent low mood, hopelessness, and impaired functioning.

Studies, including randomized controlled trials, have shown that antidepressants do not significantly reduce core grief symptoms such as yearning, sadness tied to the specific loss, or emotional pain related to missing the person.

If a grieving person shows signs of sustained despair, self-harm, or disconnection from daily life, a mental health assessment may be warranted but grief alone is not a disorder.

Numbness

Numbness is a common and often overlooked response to grief. Feeling emotionally neutral or detached doesn’t mean you’re “doing it wrong” or that the loss hasn’t affected you. It may be your brain’s way of protecting you until you’re ready to process the pain.

This can be especially true in healthcare settings, where the demands of the job often require compartmentalizing emotions to focus on patient care.

Grief doesn’t always follow a visible or expected path. Be gentle with yourself and know that emotions may surface later, in ways you don’t anticipate.

No One Way to Feel

Grief is a complex emotional experience. These emotional waves don’t just affect how we feel; they also impact how we think, focus, and function.